Next Monday I’ll be presenting a review of the firearm pictured here, but today I want to devote this blog to one of the most iconic and historically important handguns ever produced — John Moses Browning’s superlatively designed, stunningly beautiful achievement the Colt Model 1911 designed for the potent .45 ACP cartridge.

You’ve seen the 1911 before, by the way. In fact, whether you know it or not, you’ve seen it literally thousands of times over the years. And, as a purveyor of fiction, I simply must note that you’ve seen it mentioned in countless novels as well — Even agent 007 used it in Ian Fleming‘s novel Moonraker and in the short story From a View to a Kill in the For Your Eyes Only collection of works. You simply cannot escape it’s ubiquitous presence in television, movies, literature, and any serious history on the U.S. military over the past 100+ years.

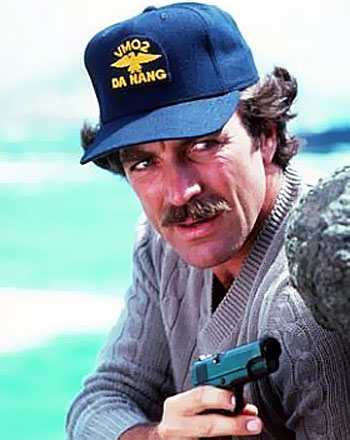

For instance it was Thomas Sullivan Magnum’s favorite weapon.

Tom Magnum on the case with his trusty Series 70 M1911— Image from Internet Movie Firearms Database (www.imfdb.org)

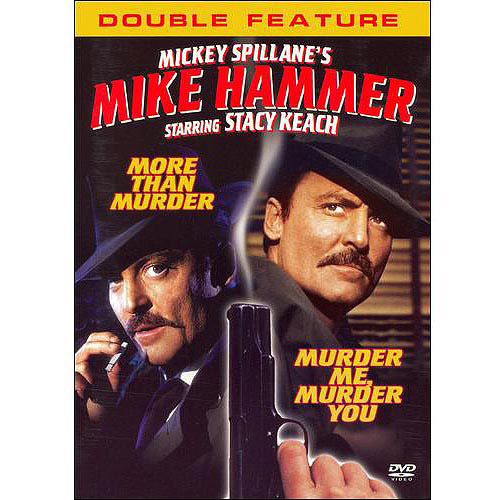

Mike Hammer called his 1911 “Betsy.”

Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer (Stacy Keach) with “Betsy”

And even John Shaft used one.

John Shaft’s M1911 — For those times when his Colt Detective Special just wasn’t enough firepower

Indeed, you’ll see an M1911 used by either the hero or a bad guy in almost any film or television show in which firearms play a prominent roll in the storyline. In real life the M1911 was used by various law enforcement agencies (and still in use by some, including certain FBI units), mobsters, gangsters, and spies.

But the Model 1911 (M1911 for short) gained its fame on the battlefields of World War I, World War II, Vietnam, Korea, etc., etc., etc. Indeed the M1911 was first adopted by the U.S. Army in early 1911 — hence the name — and was the primary sidearm of the U.S. military until it was replaced by the vastly inferior 9mm Beretta M9 (military version of the Beretta 92) in 1985.

9mm Beretta M9 — The Army’s idea of a “replacement” for the M1911

The M1911’s story with the U.S. military did not end there, however. It continues in service to this day with U.S. Marine Expeditionary Units under its new designation as the M45 MEU(SOC) pistol. More recently the USMC has acquired directly from Colt a railed version of the 1911 designated the M45A1 CQBP — Close Quarter Battle Pistol — for use by both the Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) and Marine Special Operations Command (MARSOC).

M45A1 CQBP — Made by Colt and equipped with an accessory rail

Between the original M1911 and the M1911A1 version that succeeded it in 1924, the U.S. military acquired an astounding 2.7 million copies made by Colt, Springfield Armory (the former U.S. government arsenal, and not the current company using that name), Remington, North American Arms, Ithaca Gun Company (known for shotguns), Remington Rand (the typewriter/computer company), Singer (another typewriter manufacturer), and even a maker of railroad signalling gear — Union Switch & Signal.

After World War II the U.S. military had enough M1911s on hand to last until their ultimate replacement some forty years later by the aforementioned M9 Beretta. These M1911s were refurbished as needed at the Rock Island Arsenal (not to be confused with Armscor’s Rock Island Armory brand name), the U.S. Government Springfield Armory, and other military depots and arsenals.

In other words, if you’ve seen a war movie involving U.S. troops set in time from 1911 until at least 1986, chances are you saw an M1911 in the picture. And if you’ve watched a movie concerning the U.S. Marine Corps after 1985, there’s still a good chance you’ve seen a version of the M1911.

Today everybody and his fourth cousin twice removed make some version of the M1911 — Colt (the true original), Springfield Armory (the company, not the original U.S. government armory), SIG, Kimber, Wilson Combat, Ruger, Smith & Wesson, Remington, Para Ordinance, Taurus (Brazil), Rock Island Armory (the Armscor Filipino subsidiary), and even a .22 version marked under the Walther banner but made in Turkey for parent company Umarex. That’s just a partial list, by the way. Past and present there have been well over 100 companies that have made versions of the M1911 in some form or another, and in calibers ranging from the original .45 ACP to at least ten other calibers from the diminutive (.22) to the ridiculous (.460 Rowland).

And who came up with this still popular design? Why, John Moses Browning, of course. You’ll recall that name from my series on Winchester lever-action rifles (see: Winchester Rifles — Part 1; and Winchester Rifles — Part 2), another iconic series of historic firearms. But to make a semiautomatic pistol that was still somewhat compact and relatively light, yet would stand up to the power of the .45 ACP cartridge, John Browning would have to invent an entirely new recoil mechanism. Existing locked breech mechanisms of the era were complex, costly to manufacture, and unreliable. So, what Browning came up with was a short-recoil, tilting barrel, locked breech design. A simplified form of that Browning invention is still used to this day in nearly every semiautomatic handgun made for powerful calibers beginning with the 9mm Parabellum. This short-recoil locked-breech mechanism works by briefly locking the barrel and slide together as a unit after the firing of the bullet. The slide and barrel recoil back a short distance until the barrel tilts and disengages from the “locking” mechanism affixing it to the slide. The slide continues reward, opening the breech, at which time the spent cartridge is extracted from the chamber and ejected through the now exposed port at the top of the pistol. The slide then reverses, strips a fresh round from the magazine, and forces it into the chamber before reengaging the barrel and returning to battery (meaning the slide and barrel seated fully forward into firing position atop the frame of the weapon).

Here’s a demonstration to put all that mumbo-jumbo together for you:

As the M1911 was originally developed by John Browning under contract to Colt, I’ll now stick specifically to Colt civilian models rather that even thinking of touching upon the 100+ other manufacturers and their variants. The most common Colt civilian variants of the full-size M1911 (not Commander nor Officer models with reduced length barrels and slides) are:

- Colt Government Mk. IV Series 70 (1970 to 1983) — Revised “Collet” barrel bushing that supposedly increased accuracy, but was also prone to breakage thus reducing reliability.

- Colt Government Mk. IV Series 80 (two basic versions)

- 1983 to 1988 — New internal firing pin block for additional safety against accidental discharges resulting from dropping the weapon; retained the Series 70 Collet barrel bushing.

- 1988 to present — same internal firing pin block; return to the solid bushing pre-Series 70.

- Colt Government Mk. IV Series 70 (2001 to present) — A return to the original design that drops the internal firing pin safety of the Series 80; earlier 70 Series Collet bushing replaced with original-style solid bushing

Note: The return to the Series 70 firing system without the internal firing pin block was in response to criticism that it was more difficult to perform a trigger job on the Series 80. - Colt GovernmentM1991A1 (two basic versions)

- “Old Roll Mark” (ORM) version 1991 to 2001 — Series 80 firing pin block and original, pre-Series 70 barrel bushing; plastic trigger; cheap Parkerized finish; large and, to some, ugly “COLT M1991A” roll mark on slide.

- “New Roll Mark” (NRM) version 2001 to present — As with ORM above except an anodized aluminum trigger; much more attractive brushed-blue finish (stainless steel version also available); smaller, more sedate “COLT’S GOVERNMENT MODEL .45 AUTOMATIC CALIBER” slide roll mark.

Here’s a link list to the current Colt models mentioned immediately above as well as other variations I’ve not mentioned (including the .380 ACP variant known as the Colt Mustang):

- Colt M1991A1

- Colt XSE (a high-end Series 80 derivative)

- Colt Combat Elite (tactical version of the Series 80 also available in 10mm)

- Colt Rail Gun (Series 80 version with Picatinny accessory rail)

- Colt Gold Cup (Series 80 target model with match-grade barrel, adjustable sights, and other enhancements)

- Colt Series 70

- Colt Defender (short-barrel Series 80 version optimized for concealed carry)

- Colt New Agent (another short-barrel Series 80 version)

- Colt Special Combat Government (larger, long-barrel Series 80 variant for open carry, law enforcement, and home defense)

- Colt CQBP (current railed military version of the Series 80)

- Colt .380 Mustang (extremely compact pocket pistol chambered for the .380 ACP/9mm kurz and using a Series 80 firing system and about ⅓ the weight of a typical M1911 pistol)

Remember to return next Monday to find out what it’s like to operate an M1911 (specifically an M1991A1 version) at the range, and find out why this firearm is still so popular over 100 years after its development.

Bibliography:

- .45 ACP: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/.45_ACP

- Blowback versus Locked Breech: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semi-automatic_pistol#Actions:_blowback_versus_locked_breech

- Colt’s Manufacturing Company: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colt%27s_Manufacturing_Company

- John Browning: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Browning

- M1911: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M1911_pistol

- Short recoil operation: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recoil_operation#Short_recoil_operation

Filed under: Firearms, R. Doug Wicker Tagged: Colt, handguns, John Browning, M1991A1, Model 1911, R. Doug Wicker